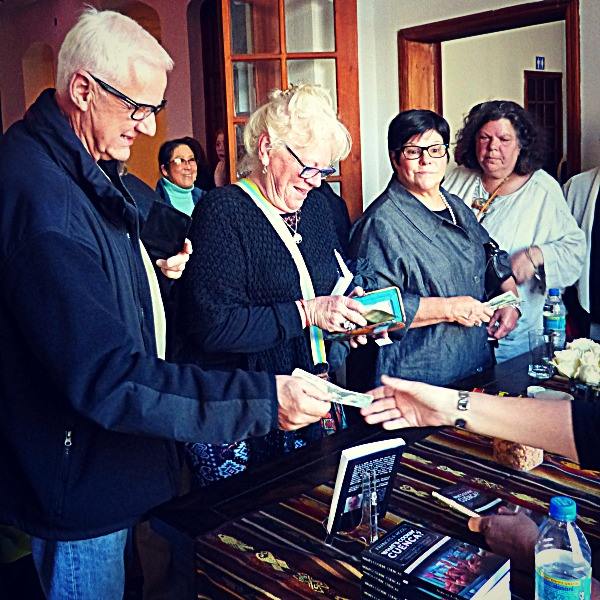

Tonight was the launch party for my book called What’s Cookin’, Cuenca? : A Gringo’s Guide to Buying and Preparing Food in Ecuador. We had a fun time with great music, dancing, food and drinks, and 120 people. My friend, Sara Coppler helped organize it. She suggested that I perform a reading from the book. Here’s a representative sample:

CHOCOLATE CHIPS are called mini gotas de chocolate (mee-nee goh-tahs day cho-koh-lah-tay), or crispas (krees-pahs) de chocolate. They are sold in plastic bags in the larger stores in the baking section. Raw chocolate is also available here. It is chock-full of caffeine (actually, theobromine) so be careful. It can keep you up at night. The small Ecuadorian chocolate chips are not very tasty. Think bits of brown Crayola crayon. The good stuff (Hershey’s and Nestle’s Tollhouse) can be purchased at Superstock or sometimes, Coral and SuperMaxi, but be prepared to pay a lot.

Not very exciting.

So I decided to write a story about cooking under challenging circumstances. People liked it. Here it is, and here am I, aspiring baker, at about the same age I was in the story:

The Joy of Cooking–with a Two-Year-Old

In 1957, my father was finishing his master’s degree in fine arts at Michigan State University on the GI Bill. He had just scored the job of Curator of Exhibits at the Natural History Museum there. My mother’s time was wrapped up in taking care of my four-year-old brother, Andy, two-year-old me, and my infant brother, Chris. We lived in student housing called “The Barracks.” A few of these Quonset huts still exist on the campus. They are used as chicken coops at the agricultural college. You can imagine how elegant they were.

My parents didn’t have a car. The closest shopping was a little store called The Quality Dairy. It also still exists. It sold a few groceries and staples, but mostly, things produced by the university’s agriculture program. It was about a mile away from our abode–which could be an uncomfortable walk with heavy groceries on a hot day in July.

Like me, my mother was a writer. I have all of her diaries, notebooks and letters. So I know about her struggles and aspirations. She was a young mother trying hard to scrape by on my father’s stipend. She was immensely proud of her beautiful children and liked to show us off. She dressed me, her only daughter, in frilly dresses, starched white pinafores, and hair ribbons. I looked like a doll but usually, within a few hours, I looked like a doll that had been dragged down a dusty road by its hair. This is not to say that anyone did such an awful thing to me! I did it to myself.

If there was a mud puddle to jump in, I jumped in it. If there was something sticky to get into, it was soon all over my face and hair and wiped down my front (hence my mother’s preference to dress me in pinafores—sort of a fancy apron). In spite of the challenge of being Franny’s mother, and the inelegance of her tiny home, my mother tried every day to meet the expectations placed upon women of her age. To be the perfect wife, to have an immaculate house, to set the perfect table, to have well-behaved and well-groomed children, ready to present to the public at any time.

So it was stressful for her when my father came rushing home at noon for lunch one day, to announce: “The museum director, Dr. Baker, and his wife are coming for dinner tonight! Can you bake a chocolate cake?”

I know that my mother loved my father because she didn’t stab him right then and there with the bread knife. She did express her unhappiness at this lack of notice, and insisted that he help her. His first job was to walk to the Quality Dairy and purchase the ingredients for dinner—a big chicken to roast and more potatoes, and if he wanted a cake baked, butter. She needed one stick for the cake batter and one for the frosting. While he was on that errand my mother would bathe me and dress me, and prepare me for my father’s second responsibility: keeping Franny clean.

Dad returned from the Dairy. Mom set the butter for the frosting on the kitchen table to soften. She prepared the chicken and vegetables, and went next door to borrow Millie Waggoner’s really big table cloth.

When she returned a few minutes later she found my father on the sofa reading a book. Little Franny, standing on a chair at the kitchen table, was happily squishing butter through her fingers.

I was two. Apparently, I didn’t express myself with words, but with actions. To express dismay when someone said, “Franny, no!”–I would screw up my face, start to cry, and run my fingers through my hair.

Before she thought to stop herself, my mother moaned, “Franny, no!”

“You said you’d watch her!” she hissed at my father, as she bathed me for a second time and washed my buttery-blond hair. She dressed me in another clean, ruffled dress and another starched white pinafore. “And now you need to get me another stick of butter! Take the kids with you and don’t you dare let Franny out of your sight!”

And so, leaving my mother to furiously slam the roasting pan with the chicken and potatoes into the oven, we took off. My dad pulled the wagon and my brothers and I went along for the ride to the Quality Dairy.

When we got back, my mother was not amused.

Of course, when my father arrived at the store he had forgotten the purpose of his shopping expedition. He bought everything but butter. He bought milk, cottage cheese, eggs, flour and chocolate ice cream. Chocolate popsicles, actually. We’d finished eating them on the way home, but they had melted down our hands, were smeared on our clothes and all over the faces.

“Oh, Franny!”

Oh, no…

“You bathe her this time!” said my mother. “I’ll go get the butter!”

She left my father to wash the chocolate out of my hair, grabbed her pocketbook and stormed out of the house. She fumed as she trudged down the road, went into the store, found the butter, waited at the cash register for her purchase to be rung up, opened her purse and pulled out—cookie cutters. Her purse was full of cookie cutters. No wallet. No house keys. No hairbrush. No lipstick. No handkerchief. Just cookie cutters.

Practically at the end of her rope, she struggled back to our house where my freshly scrubbed brother Andy ran out to meet her, yelling, “Franny can’t get out!”

Apparently, after bathing me my father had left me for a moment while he went to find something for me to wear. Ever curious in his absence, I had inspected the door latch and managed to lock myself in. The only key was the one on my mother’s missing key ring. My father’s next attempts to open the door with a variety of screwdrivers and metal chisels were in vain.

So for the next hour or so while my mother searched for the former contents of her purse, my father and several of the other Barracks daddies found and set up a ladder, jimmied open the bathroom window, hoisted Andy through it and told him how to open the door. Success!

My mother was less successful in finding her keys. She had not thought to look in the narrow place behind the sofa that only Franny was small enough to explore. It was not until a year later, when my parents were loading up the furniture for our move to our big house in Williamston that my secret cache of animal crackers, toys and other treasures—including my mother’s wallet, key ring, and lipstick–were discovered tucked into a hole in the fabric of the back of the sofa.

But! Too late for more butter! No time to starch another pinafore! Dr. and Mrs. Rollin Baker arrived to find the neighbors still thronging around the front door, the ladder lying in the yard, and a tiny, tow-headed girl wrapped in a white towel sitting on the porch steps.

My mother later wrote that the dinner was good. Instead of frosting, she laid a paper doily over the cake and sifted powdered sugar on it to make a lacy design. The Bakers, who were themselves doting parents, thought the whole story was hilariously funny. Decades later, when I met Dr.Baker at a University event, he told me that it was the most wonderful dinner party he and his wife had ever attended.

2 Comments

What a wonderful “slice of life”. Thanks for sharing this story.

I am still laughing at the story of you as a two year old. It is amazing just how much trouble a young child can get you into. Thank you for such a wonderful story, which reminded me of my own travails with my daughter when she was little.

My friend, Heather, presented me with an autographed copy of your book, “What’s Cooking Cuenca?” and I am thoroughly enjoying its pages, the information you have provided and your delightful stories and recipes. We have been living in Cuenca now for 3 weeks and find it amazing that anyone can find where people live. Being able to draw a good map works wonders.

Your wonderful book is a god send and now I won’t have to use Google Translate for try to get help finding what I need. Google Translate doesn’t always give you the correct word when you need it.

Thank you again for a delightful and informative book. Who knows, perhaps one day I will have the pleasure of meeting you in person. If you are ever over by the Monay Shopping, give me a shout. I’ll come get you rather than try to explain how Pumapongo changes to Tuahntinsuyo and where we are!

Comments are closed.